Rats Against Invasion

On the resistance of Philippine forests and native fauna against introduced rat species. Also, looking for Master's topics.

Invasive rats are bad news for island communities. They pilfer food, spread disease, feast on crops. Just as bad, they crack open snail shells and prey on nestlings. Marauding rodents have been implicated in the eradication of dozens of species on numerous islands. Look up the last song of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō in Hawaii, or the poor Aldabra Brush Warbler of the Seychelles, both birds now long since vanished with the wind.

Understandably, then, it's easy to become concerned for native Philippine fauna. With so many imported Rattus running around – apart from the burly and oversized R. norvegicus, likely delivered to the country by European ships, there's also R. exulans, the Polynesian rat, and R. tanezumi, the spiny rice field rat - one worries about the havoc they can cause to local ecosystems. After so many victorious conquests around the world, just how deeply can these whiskered invaders infiltrate the country’s forests?

The answer, surprisingly enough, is not a lot. Or at least, not in those areas where old-growth forests yet stand whole and stubbornly intact.

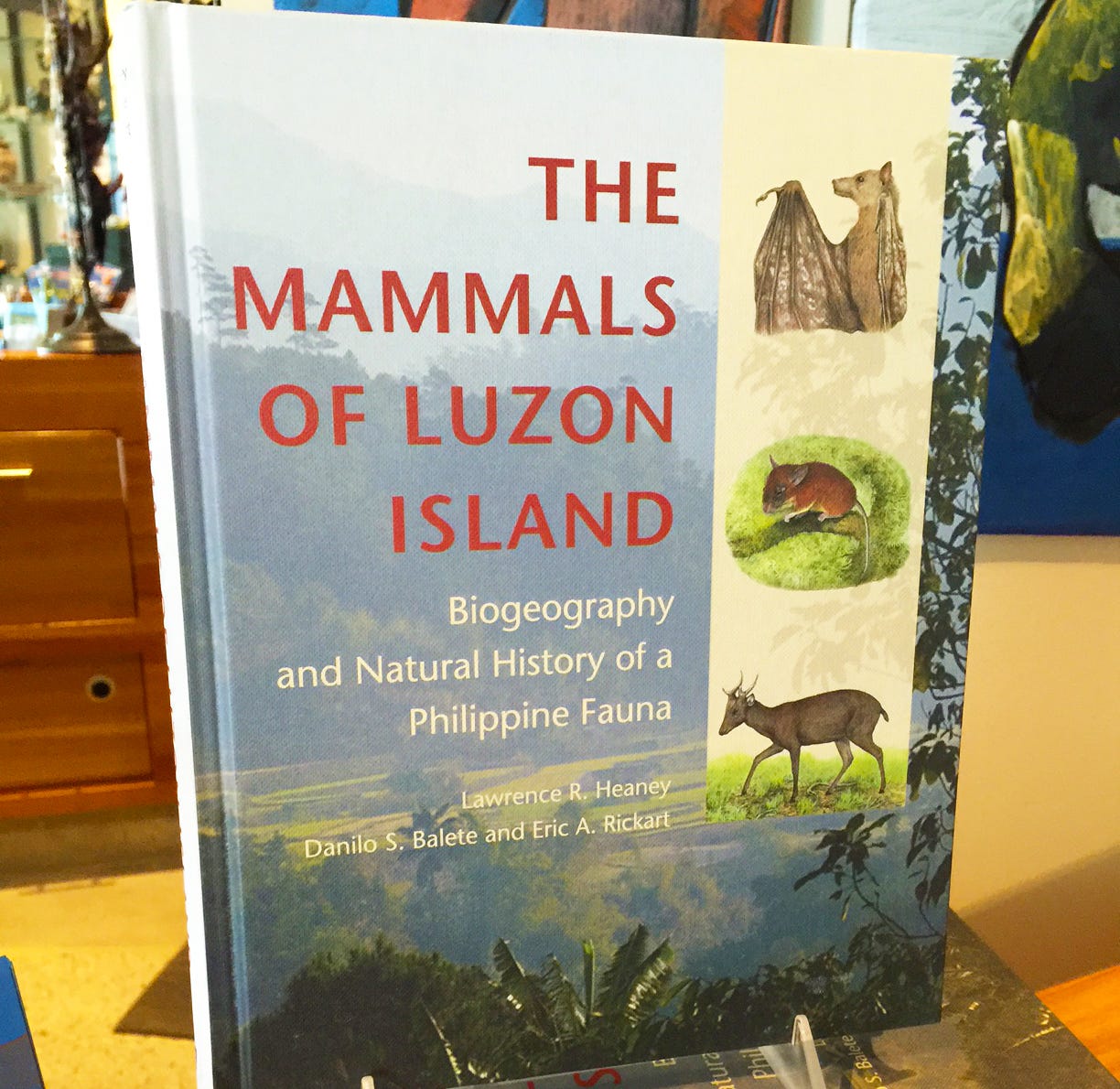

I don't intend to minimize the impact of invasive species, far from it. Recently, however, while I was agonizing about future Master’s studies, I remembered a tome I first read doing research for my undergraduate thesis, titled The Mammals of Luzon Island: Biogeography and Natural History of a Philippine Fauna, authored by Lawrence Heaney, Danilo Balete, and Eric Rickart.

For over a decade, the authors and their team climbed over a dozen mountains on the Philippines’ largest island, recording close to thirty new species and learning much about the ecology of its’ mammals in the process. The discovery of so much unsuspected diversity in what was once considered a well-documented region would have been remarkable enough. But apart from that, they noticed another, equally unexpected phenomenon.

At the time, the accepted scientific rule-of-thumb was that island fauna were particularly vulnerable to invasion; the wildlife in the many atolls of the Seychelles suffered terribly from introduced rat species. Yet the deeper the authors went into Luzon’s forests, the fewer invasive rats they found.

What they observed, over and over again, was that invasive rats thrived wherever habitat disturbance was severe, but struggled where it was mild. You can find lots of R. tanezumi in coconut plantations, and just as many in rice fields, but not much in young jungles newly regenerated from decades of logging. And in ancient old-growth forests more or less untouched by human industry, they were virtually absent. Instead, in these latter more verdant places, it was their native counterparts who prevailed.

Because the Philippines, as the authors found out, harbors what appears to be one of the greatest concentrations of native rodent diversity in the world. In other words, the country has lots of homegrown rats and mice. There are cloud rats, earthworm mice, shrew rats, rats that burrow through the ground, mice that live in trees. Some eat leaves, others munch on worms, yet others forage for fresh shoots, soil invertebrates, seeds. These animals bear little resemblance to their foreign cousins. Just look at this photo of the soft-furred northern Luzon giant cloud rat.

When forests are healthy, native rats flourish, invasive rats don’t, and vice-versa. Why? The authors hypothesized it had something to do with Luzon’s long and complicated geological past, and its consequently rich evolutionary history.

Although a complete description of the process would take far, far too long to explore here, Luzon is essentially a combination of multiple, perhaps around a dozen, different islands that emerged, grew, and joined together over tens of millions of years. Deep-sea geological activity pushed underwater volcanoes up through the surface of the sea; the built-up detritus of repeated eruptions caused these furious young islands to grow larger and larger, until they coalesced; through time and cooling magma the tops of these volcanic islands solidified to become higher and higher mountains mantled by lush forests.

The atolls of the Seychelles are very small. Kaua’i, the oldest of Hawaii’s islands, is only around five million years old. The sleeping volcanoes that comprise the Central Cordilleras first erupted about 30 million years ago. Relative to younger, smaller islands, Luzon’s ancient mountains with their variety of habitats, from the cool moss-covered forests near the peak to the steaming jungles surrounding the base, gave life both more time and more space to evolve into many different forms.

This primeval diversity formed the basis of the authors’ hypothesis. Luzon’s wide variety of native rodents are well-adapted to their environment, having evolved in the face of both volcanic eruptions and raging typhoons for millions of years. Think of it this way: on a small Pacific island freshly risen from the sea, life will only have had enough time to learn the basics of basketball. But on Luzon, it has had time to practice advanced tactics and strategy, and develop specific players to fill the role of point guard, power forward, and center.

Cut down the forest, and the natives lose their home-court advantage. But as long as the trees are left standing, they will forage for food better, find shelter faster, and evade predators more efficiently. Faced with such stiff competition, invading rats simply can’t get a foot in. Or at least, that’s the idea.

As the authors of Mammals of Luzon explain, their hypothesis has not yet been rigorously tested in the field. There is too much about the ecology of native mammals, from breeding behavior to habitat use, that remains uncertain. As far as I can tell, no detailed studies have been made about the interactions of native and invasive rats in the wild.

That said, the resistance of Luzon’s forests and their native fauna to invasive rats isn’t just a hypothesis. It’s a well-documented observation borne by years of tough surveys and exhaustive rodent trapping. Whatever the reasons for this resistance may be, one thing is clear: our forests are citadels against invasion only if they remain intact. All the more reason, then, to nurture and protect them.

I wrote this article while preparing for future graduate studies. I thought a good approach would be to think of a possible Master’s topic first, and then look for potential mentors and universities based on that. Looking for ways to test the hypothesis that the Mammals of Luzon Island formulated above seemed like an interesting place to start.

One way to explore the competition hypothesis stated above would be to compare the characteristics of native and invasive rodent populations in sites where: i.) only native species are present, like a mountaintop forest, ii.) where both native and invasive species are present, perhaps a regenerating jungle, and iii.) where only invasive species are present, maybe a vast coconut plantation.

If invasive rats were being outcompeted for food, then they should get scrawnier the deeper into the forest they go. The body mass of individual rats should decrease. Their diets may also change. Hypothetically speaking, they might shift from eating their favored earthworms to ants, because in the forest the natives eat up all the earthworms before anyone else can get to them.

The longer I considered the question, the more I realized just how much information would be needed to even begin to answer it. You’d need to study the population dynamics of both native and invasive species across different forest types and elevation gradients, measuring changes in survival, fecundity, and juvenile recruitment. You would need to test how their habitat use changes, and how they behave toward each other in the wild.

Complicating things is the fact that there’s still so much about the Philippines’ native rodents that we don’t know. Are they monogamous? Polygamous? Do they form large social groups like meerkats, or are they more solitary? Are they territorial? If yes, how large are their territories? Do they patrol their territories to protect scant food resources, or to cordon off potential mates, or both? What kinds of food do they most like? Where do they sleep? Do they dig burrows to nest in, or use existing tree cavities for shelter?

For many species these are still very much open questions. And despite the difficulties that I’ve heard about when studying rodents (they’re small and usually secretive animals, and are hard to capture and monitor), to me they’ve always seemed like particularly tantalizing animals to study.

If you’re interested in reading more about rats and the like, I’ve listed my references below. The next biology-oriented blog post will probably about the movements of fruit bats. Until then, thanks for reading!

References

Gurnell, J., Wauters, L. A., Lurz, P. W., & Tosi, G. (2004). Alien species and interspecific competition: effects of introduced eastern grey squirrels on red squirrel population dynamics. Journal of Animal Ecology, 73(1), 26-35.

Heaney, L. R., Balete, D. S., & Rickart, E. A. (2016). The mammals of Luzon Island: biogeography and natural history of a Philippine fauna. JHU Press.

Heaney, L. R., Balete, D. S., Duya, M. R. M., Duya, M. V., Jansa, S. A., Steppan, S. J., & Rickart, E. A. (2016). Doubling diversity: a cautionary tale of previously unsuspected mammalian diversity on a tropical oceanic island. Frontiers of Biogeography, 8(2).

Harper, G. A., Dickinson, K. J., & Seddon, P. J. (2005). Habitat use by three rat species (Rattus spp.) on Stewart Island/Rakiura, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 251-260.

Harper, G. A., & Bunbury, N. (2015). Invasive rats on tropical islands: their population biology and impacts on native species. Global Ecology and Conservation, 3, 607-627.

Harris, D. B., & Macdonald, D. W. (2007). Interference competition between introduced black rats and endemic Galápagos rice rats. Ecology, 88(9), 2330-2344.

National Academy of Sciences. (2004). Scientific Research Has Revealed How the Hawaiian Islands Originated. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK208869/

Russell, J. C., Cole, N. C., Zuël, N., & Rocamora, G. (2016). Introduced mammals on western Indian Ocean islands. Global Ecology and Conservation, 6, 132-144.

Sykes Jr., P. W., A. K. Kepler, C. B. Kepler, and J. M. Scott (2020). Kauai Oo (Moho braccatus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.kauoo.01