Captain Jack Aubrey Has Me by the Lee

All about Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World and Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series!

There are two movies my father is forbidden from watching with his family. The first is Gladiator. The second – also starring Russel Crowe, and Gladiator’s only rival, in terms of thousands of times played on the TV – is the thundering naval epic Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World.

Released last 2003, director Peter Weir’s two-hour long screenplay opens with some dire text on black background: “April, 1805 – oceans are now battlefields.” The Napoleonic Wars are in full swing. French privateer Acheron sails for the unguarded shipping lanes of the fat Pacific. To protect Her Majesty’s vital commerce, the British Royal Navy sends Captain Jack Aubrey, commanding the crew of the 28-gun frigate H.M.S. Surprise, and accompanied by his friend and brilliant physician Stephen Maturin. So begins a deadly cat-and-mouse game which takes the pair from the blue Atlantic to the storms off Cape Horn and beyond.

Every so often, during particularly lazy weekends, as the family considers what to do for the evening, my father will make a brave attempt towards suggesting one of his two favorite pastimes (the other being Gladiator). “What about watching Master and Commander?”

At which point everyone else will immediately vote him down, my sister and my mother and I in a united front, 3 against 1. Absolutely not. It was great the first time, but at this point it feels like we’ve almost memorized the entire script.

My father, unfortunately, has no allies. Until recently, that is.

A few months ago, while browsing my father’s bookshelves, I spotted a familiar title. Master and Commander. “You mean, like the –?” “Yes, like the movie,” he replied.

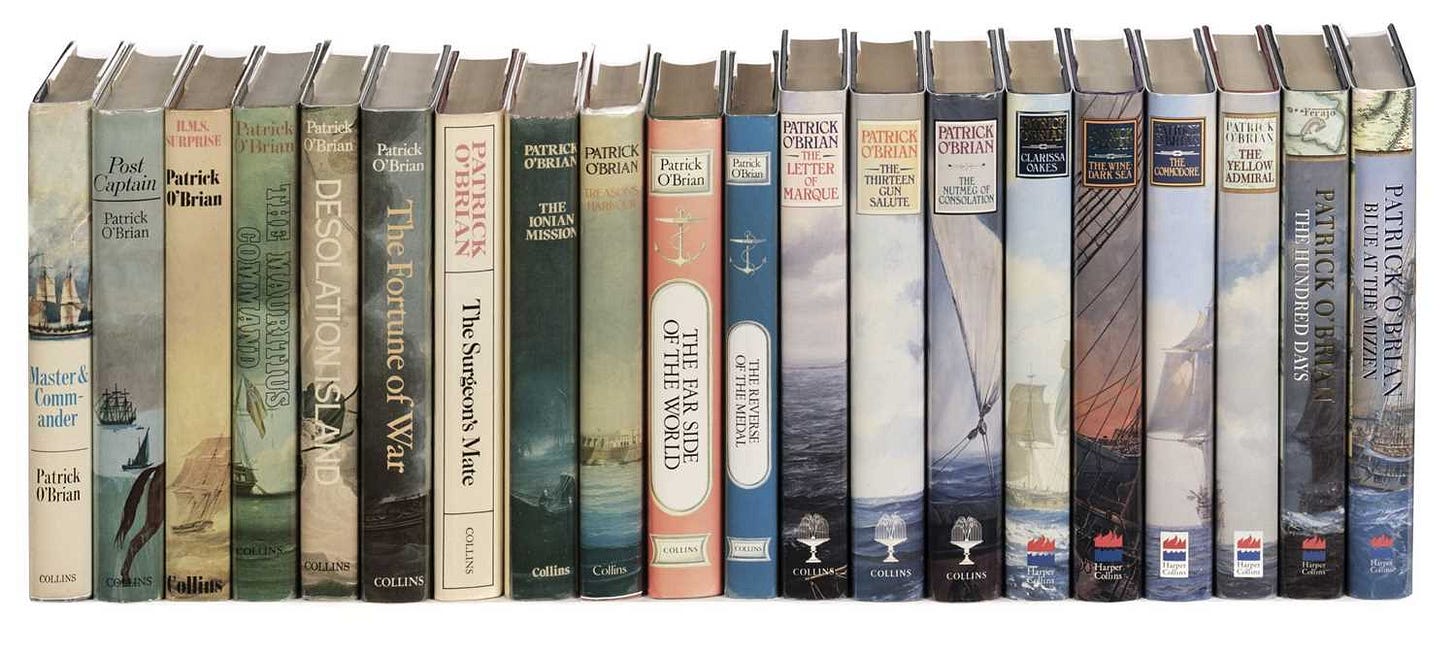

Surprise! Apparently, the entire screenplay was adapted from a book, or should I say books: the Aubrey-Maturin series by author Patrick O’Brian. The volume I had just encountered was the first of twenty-one installations. It was a fresh delivery. For years my father had been reading and re-reading the 10th in the series, The Far Side of the World, in his usual habit of consuming a series horrifically out of order. Until finally he decided to try going at it properly, from the beginning. Like any decent person should, I thought.

Out of curiosity, I flipped the book open. The story began not with cannon fire, but with music:

The music room in the Governor’s house at Port Mahon, a tall, handsome, pillared octagon, was filled with the triumphant first movement of Locatelli’s C major quartet…

Aubrey is in the audience. Entranced, he thumps fist to knee keeping time with the orchestra. The quartet rises, soars. Our good hero is on the verge of spontaneous applause. Aubrey turns to a neighbor to express his sheer delight, only to be met with a reptilian stare. “If you really must beat the measure, sir, let me entreat you to do so in time, and not half a beat ahead.”

Thus starts one of the most celebrated friendships in fiction, one that almost ends before it begins in a near-duel, only to be saved by Aubrey’s natural good cheer and the pair’s shared love for music. The doctor Maturin eventually joins Aubrey on his first command to become the ship’s surgeon.

For a naval novel, the opening chapters take place almost entirely on land. There are so many things to prepare when you are a new captain, supplies and crew to procure, obnoxious commandants to outmaneuver, a sweetheart (coincidentally also the commandant’s wife) to visit. And all this in the sultry environment of Port Mahon, the hot Menorcan sun, the Mediterranean breeze, dhows and tartans and looming men-of-war docked along the quay, prostitutes and off-duty sailors carousing between the spilling bars and cafes. It takes well over a hundred pages before the first whiff of gunpowder, that first booming crack of four-pound shot piercing the smoky air –

– Hold on, I’m already over a hundred pages in?

I finished the first installment in a week. The second, Post Captain, needed two weeks, but only because I was so busy with work. Afterwards, to pace myself, I took a break, reading novels by Peter Matthiessen and Alvaro Mutis. And then I went straight back to the third book, H.M.S Surprise, which I’ve now finished. Book four is next. Books five, six, and seven were delivered just yesterday. I have no idea how it happened, but I’m hooked.

O’Brian, as many others have said, makes no concessions towards readers unfamiliar with nautical terminology. What the hell is a mizzentop? Or a sail two points off the starboard quarter? But then, like a freshly pressed lubber learning the ropes, you slowly learn the shape of your vessel, which parts lie fore and which aft. You are absorbed into the rhythms of the crew and their slang. See here you cove, the horror of a lee shore is this: it means the ship is caught between land and the wind blowing it against a waiting reef. Now listen to the rigging sing as it strains against the breeze.

The reward for your hard work is immersion. Every Aubrey-Maturin novel is a portal to the Age of Sail. And it’s a shockingly engrossing place, all the more so when you catch the unsettling threads peeking out in between the period-accurate descriptions of societal norm and dress. For all their gallantry, Aubrey and friends are still agents of empire. One of his British Navy officers used to work on a Guineaman - a ship that ferried slaves across the Atlantic. To prevent the loss of chattel to suicidal despair, he would use the whip. “We used to save a good many by touching them up with a horse whip in the mornings.”

To my relief, the good captain and his doctor friend have so far managed to steer clear of such direct participation in brutality. They make for a fascinating duo, and one of the main reasons to keep reading. One is a daring, gregarious, genius seaman of a Tory (read: conservative monarchist), yet one who is also often rendered completely inept by life on land. The other is an irrepressibly melancholic Irishman, keenly intelligent, of liberal inclinations, accomplished in medicine and natural history and espionage, but with a wonderfully acerbic distaste for good hygiene.

It’s an unlikely friendship, one characterized by mutual devotion and loyalty, and perhaps Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major. Just read this GQ article on why Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World is a beacon for positive masculinity.

Incidentally, the two were also responsible for one of the more galling moments in my life recently. It happened over dinner. My father was talking about the quality of Master and Commander’s casting. He praised Paul Bettany – who also played Vision from the Marvel movies – and his portrayal of Stephen Maturin, to which I agreed.

And then he started talking about Russel Crowe, who plays Aubrey.

No, no, I replied. I must disagree. I love Crowe, but he’s too serious, too dour! He has the gravity but not the cheer. He lacks a certain quality of joy. In the books, when Aubrey jumps into battle, the man is described as seemingly multiplying in size, he literally glows -

– And then I noticed my father smirking at me, a smug look on his face.

Goddamn it. Captain Jack Aubrey has brought me by the lee.

I just visited the Spanish Museo Naval in Madrid, which had me oscillating between horror at the lack of even who’d of historical reflexivity, and memories of Master and Commander pingponging through mind and heart. Your writing invites me to cherish and rethink both. BTW, when in Madrid, don’t miss it! Well worth a half day - and it’s free.

What a huge pleasure, and now i'm going to start in on the books and maybe the movie! A huge pleasure as in a glorious piece of writing, not least because of the fun family story behind the story about the O'Brian stories..... Thank you Rio!